Beginner’s Interactive Fiction, Part Two: ChoiceScript in Half an Hour

“ChoiceScript” is a tool created by Dan Fabulich, used by the company Choice of Games. I am not associated or affiliated with Choice of Games in any way, but ChoiceScript is my preferred writing tool and I believe it is better suited to long-form stories than any other. It is simple enough for non-coders to use and complex enough to have a great range of clever tricks and features.

STEP ONE: Go to ChoiceOfGames.com, which looks like this (the feature story varies):

Click on “Make Your Own Games” (in the top row of tabs) and the next screen will look like this:

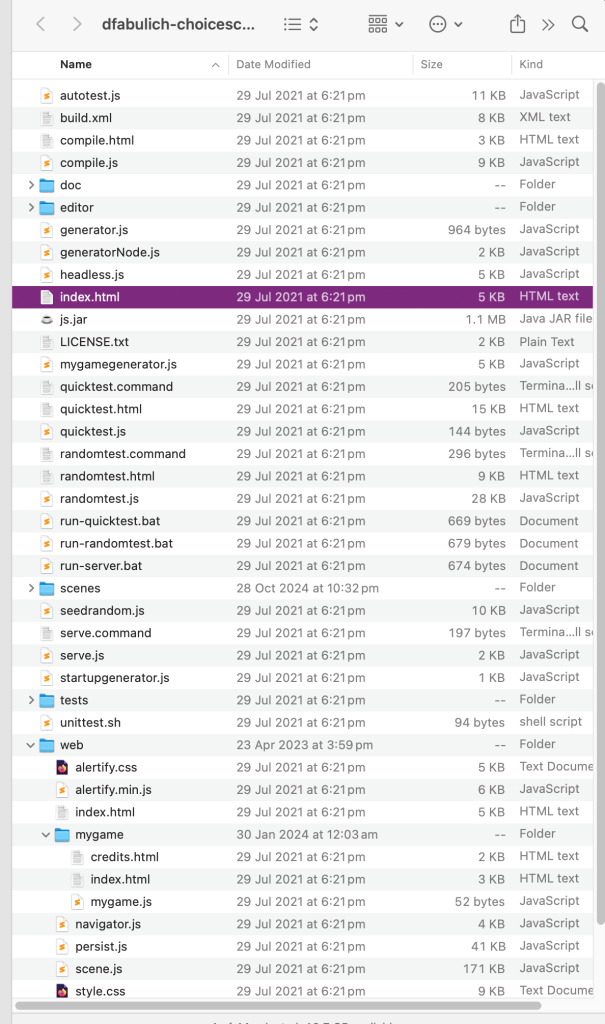

STEP TWO: Download ChoiceScript following their instructions on that page. For me it looks like a folder on my desktop.

STEP THREE: You will also need to have or install a text-only program such as Text. I use a power Mac and the text program I use is called Sublime Text. It is free (although I chose to purchase it after using it for a while).

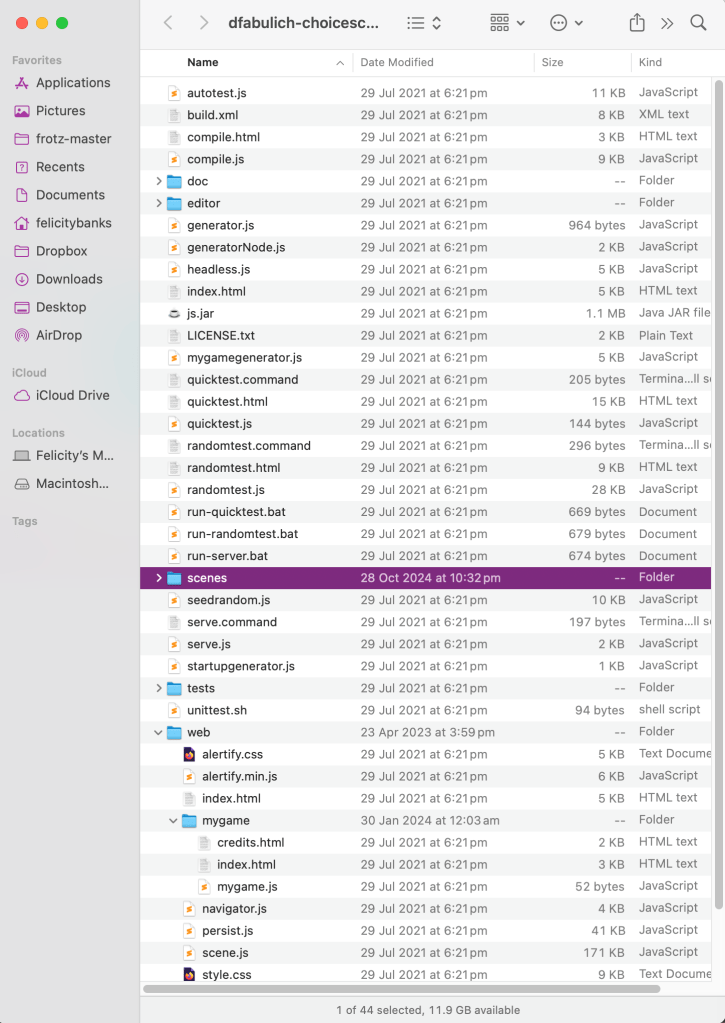

STEP FOUR: When you download ChoiceScript, it has a small piece of story already set up for you, so you can begin writing by simply replacing their words with your own. To access it, open your ChoiceScript folder, then the “scenes” folder (highlighted in the first image below), then the “startup.txt” file (making sure it opens in your plain-text program). It may just be called “startup”.

Inside, you will see something like this (after scrolling down):

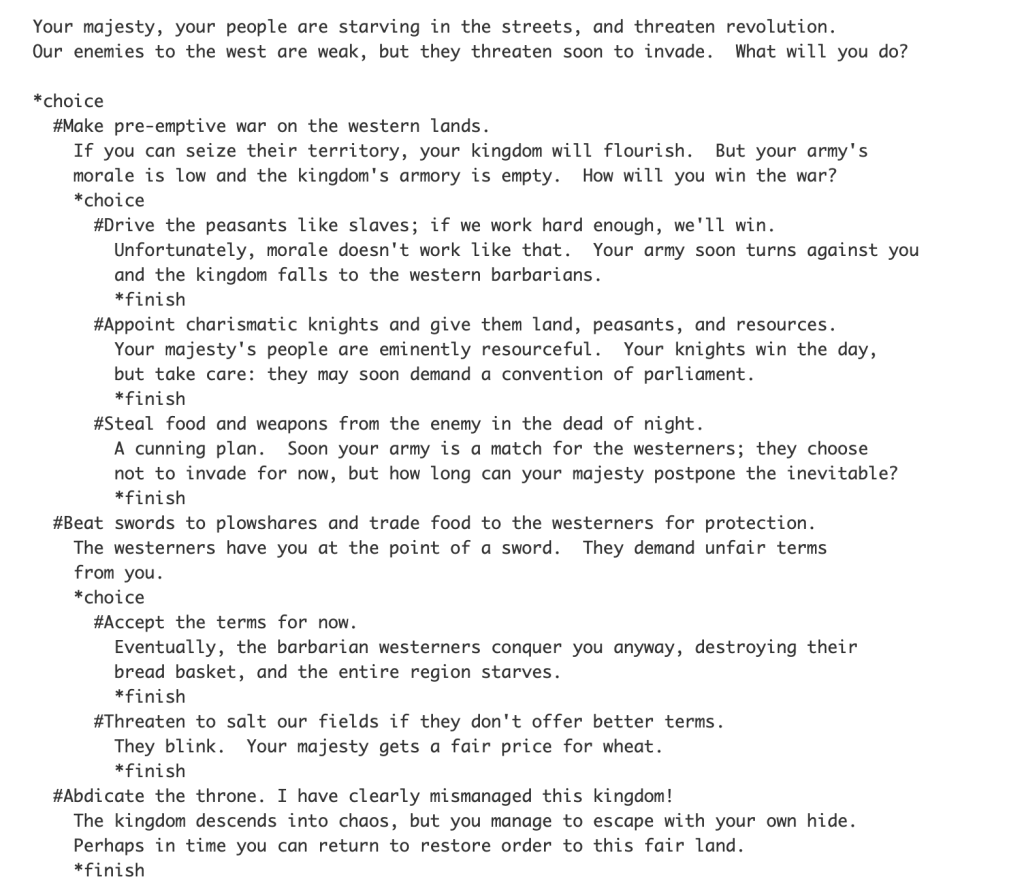

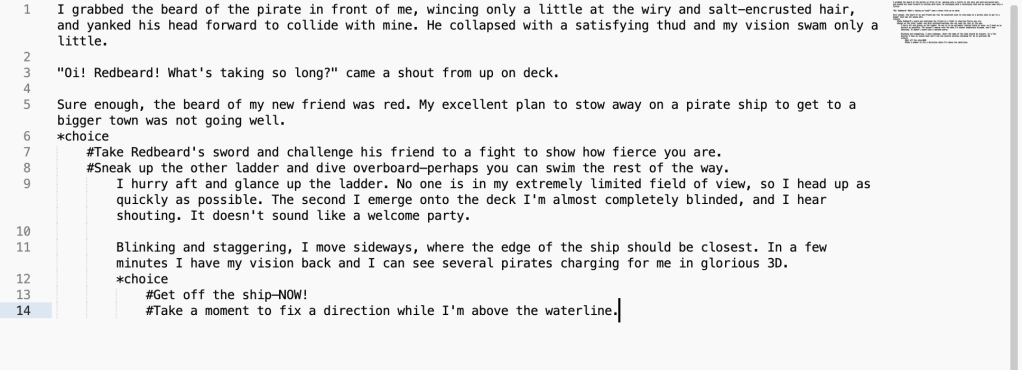

So that you can compare ChoiceScript with Twine, here is the exact scene we started writing in my Twine in Five Minutes entry—as it would appear in a ChoiceScript file. This is what it looks like in ChoiceScript after writing the first paragraph and first set of choices:

Note there are line numbers on the left. They will be extremely useful when you are debugging your story, as the automatic testers tell you what line your mistakes are on.

And this is what it looks like after we’ve added another choice INSIDE the second choice (the same choice we did in the Twine story). Readers only see the second pair of choices if they took the second path.

That’s as far as we got with our Twine story.

As you can see, indents are extremely important in ChoiceScript. So are the symbols “*” and “#”.

Note that the word “choice” is always written in lower case. This is true for all the commands that you will use in ChoiceScript.

Tip: Programs need precision. Commands must always be in the exact same form (no capital letters, ever, and usually no spaces). A tab or space in the wrong place can break your game.

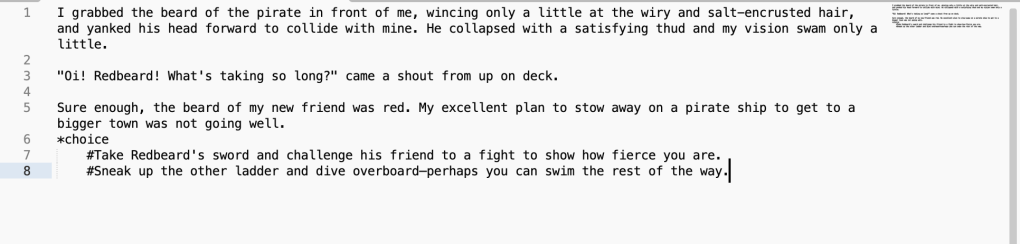

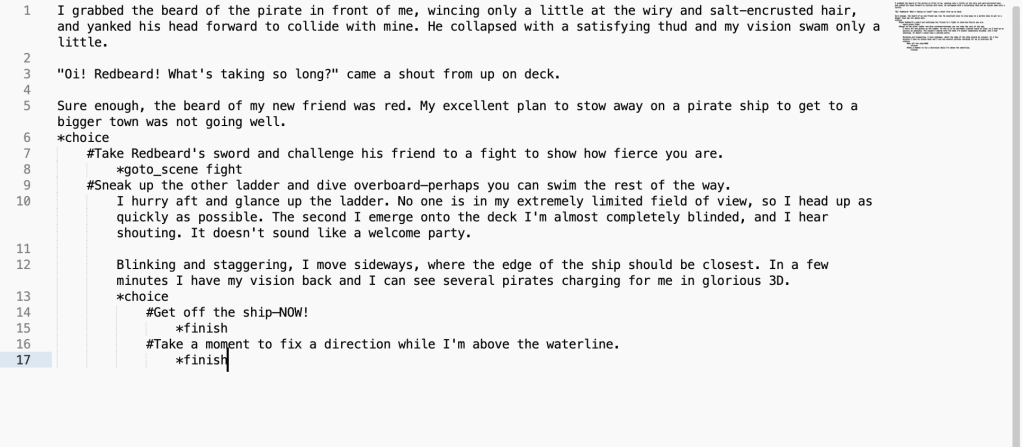

This section of story won’t actually work yet. You need to tell the program where to go after a choice is made. Your options are to go somewhere else in the file (you can even go back to the start if you really really want) or to another file. In ChoiceScript, you have a new file for each chapter. You can even have entire scenes that are only read if certain choices are made. Usually, you end a chapter with “*finish”, and the story automatically goes to the next chapter.

So here’s the same story but with all the loose ends tied up. One choice leads to a unique scene. The other choice will go to the next chapter.

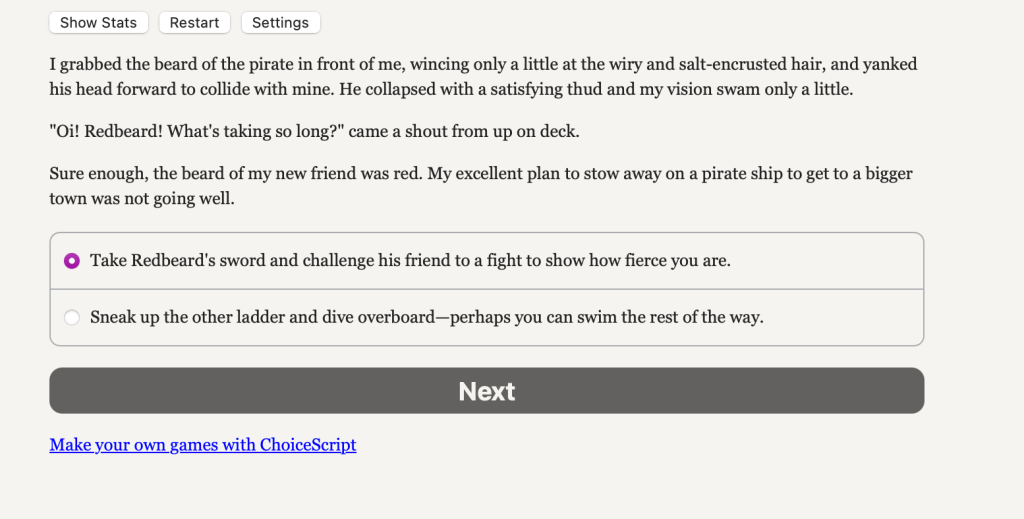

From here, you can test the story if you like. Click on “index.txt” (or “index”) from your original ChoiceScript folder and it will open up your story.

You may have to select the ChoiceScriot folder to run it. The story looks like this for the player:

STEP FIVE: Now might be a good time for a break.

Okay? Okay!

Go to the very first line of your “startup” file and you should see three commands, each marked by an asterisk.

*title

*author

*scene_list

Write in your title and your name, with normal capitalisation, like this:

*title Pirates!

*author Felicity Banks

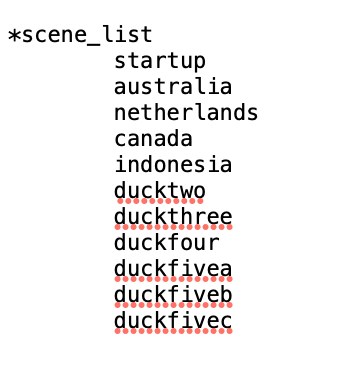

Your scene list is the list of… well, scenes. You can easily add to it at any time. I tend to use numbers, with some part of the title so they’re different to all my other stories. If I have ‘special’ scenes I’ll give them special names. The scene list tells the program what you want included, and in what order. They have to be lower case, with no spaces, and numbers must be written out in full. The first scene must still be called “startup.txt”. That can never be changed. Here’s an example scene list for a story that has four opening chapters and three final chapters.

STEP SIX:

Now we get to the use of statistics—the mechanism the program uses to keep track of the choices made by the player. THIS is what makes ChoiceScript so useful. Don’t worry—you don’t have to do ANY maths.

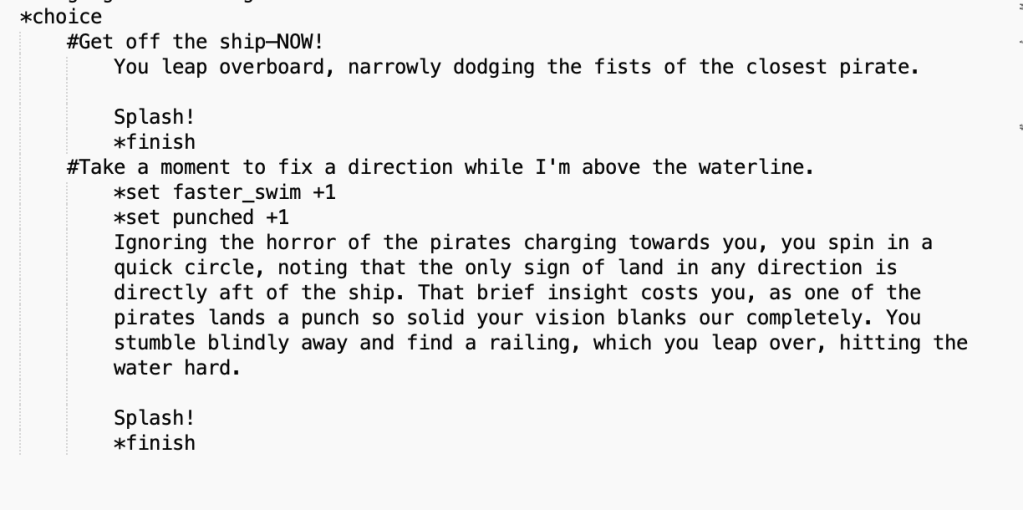

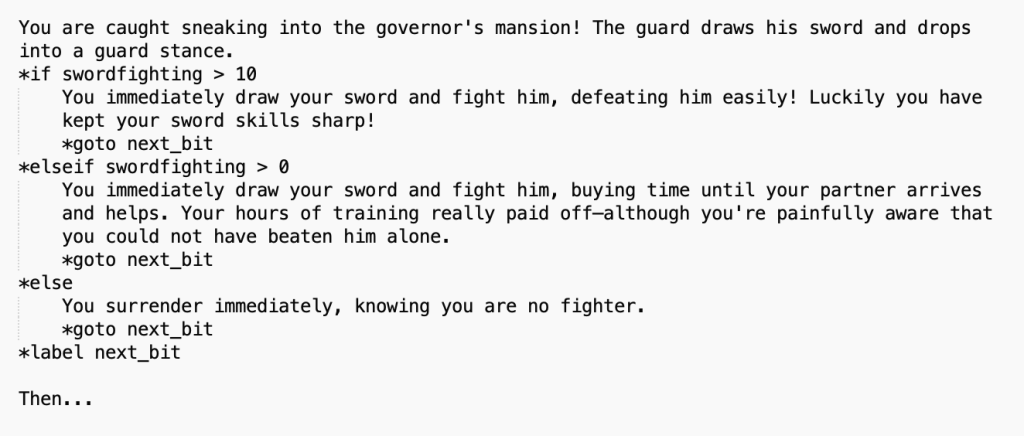

In the second set of choices above, both “Get off the ship—NOW!” and “Take a moment to fix a direction while I’m above the waterline.” go directly to the next scene. So, what was the point of that choice?

As writers, we should add some text to the choice to make it more worthwhile. But we can do more than that—we can establish through the text that the player character gains an advantage and/or a disadvantage from this choice.

FIRST we need to invent the stats we want. In startup, after the scene list, we invent our stats and their starting value like this:

*create faster_swim 0

*create punched 0

Writing Tip: You may automatically invent familiar statistics, like Health, or Strength, or Beauty, or Intelligence. But Choice of Games loves unique and interesting stats, like “Disdain” or “Drunkenness” or “Introversion”.

Then, in our choice, we can change the value of those two statistics, like this:

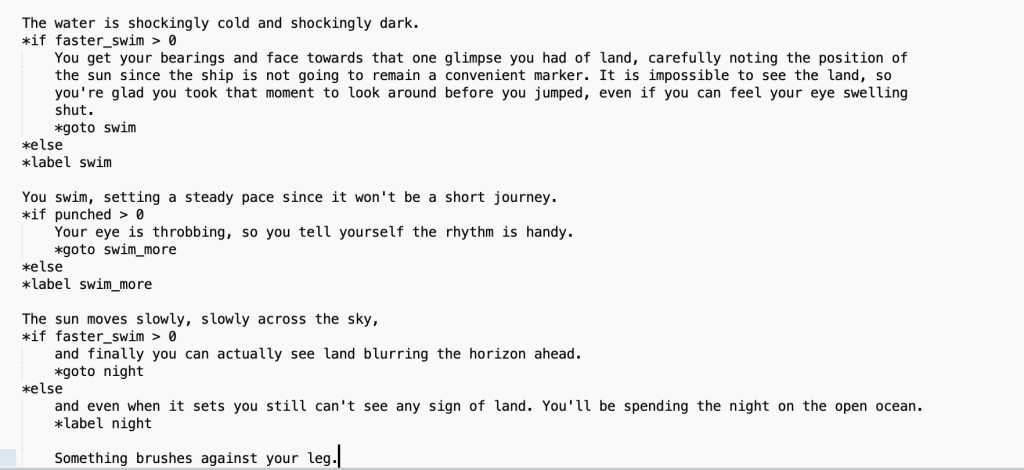

Later (probably in the next chapter but it may not make a difference for several chapters), when we want to show the results of those statistical changes, we do it like this:

The player who chose to look around before jumping overboard gets this text:

The water is shockingly cold and shockingly dark. You get your bearings and face towards that one glimpse you had of land, carefully noting the position of the sun since the ship is not going to remain a convenient marker. It is impossible to see the land, so you’re glad you took that moment to look around before you jumped, even if you can feel your eye swelling shut.

You swim, setting a steady pace since it won’t be a short journey. Your eye is throbbing, so you tell yourself the rhythm is handy.

The sun moves slowly, slowly across the sky, and finally you can actually see land blurring the horizon ahead.

Something brushes against your leg.

The player who didn't look around before jumping overboard gets this text:

The water is shockingly cold and shockingly dark.

You swim, setting a steady pace since it won’t be a short journey.

The sun moves slowly, slowly across the sky, and even when it sets you still can’t see any sign of land. You’ll be spending the night on the open ocean.

Something brushes against your leg.

Note the commands "*goto" and "*label". That pair of commands are extremely useful. Note also the command "*else". If you use an "*if" command, you also need the "*else" command to tell the program "continue here".

These two stats (“faster_swim” and “punched”) are boolean stats, meaning they are merely yes/no. Most stats are much more flexible, which gives your player the ability to build up skills or rapport or even their personality in a series of choices throughout the story.

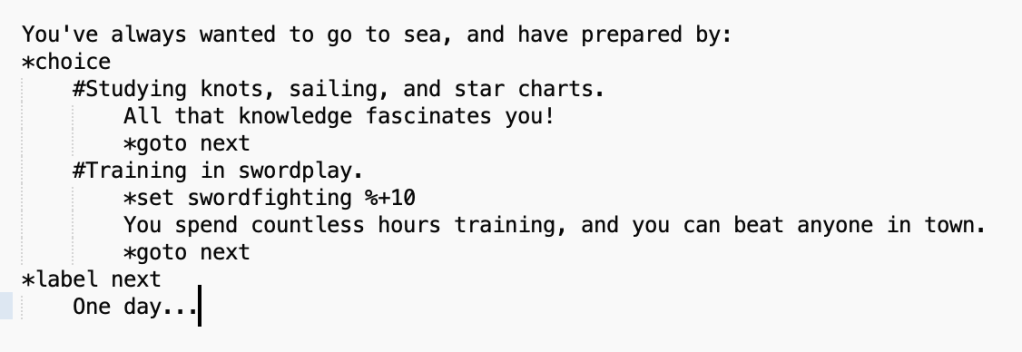

You create non-boolean stats in the same way; by the “*create” command just under your scene list, and a numerical starting value. Often you have a starting value of zero, but for some statistics you might start with 50 (50%) to indicate a neutral starting position (so you can add OR SUBTRACT from that statistic) or some other value. Here’s an example.

First, you make the statistic.

*create swordfighting 0

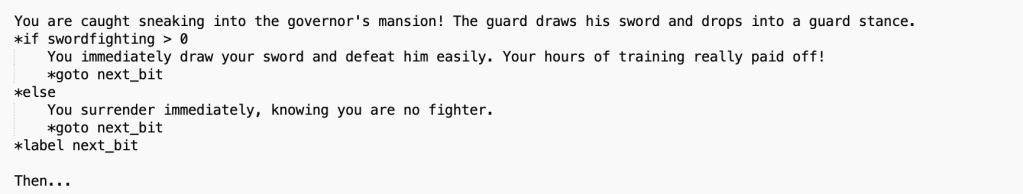

Then, you create opportunities for the player to gain that statistic.

Later, you can test them, like this:

You can also vary a test to see if a player is unskilled, slightly skilled (has chosen swordfighting skill at least once), or extremely skilled (has chosen swordfighting skill at least twice), like this:

Note that you cannot use “*if” twice in a row. You need to use “*if” then “*elseif” then “else”.

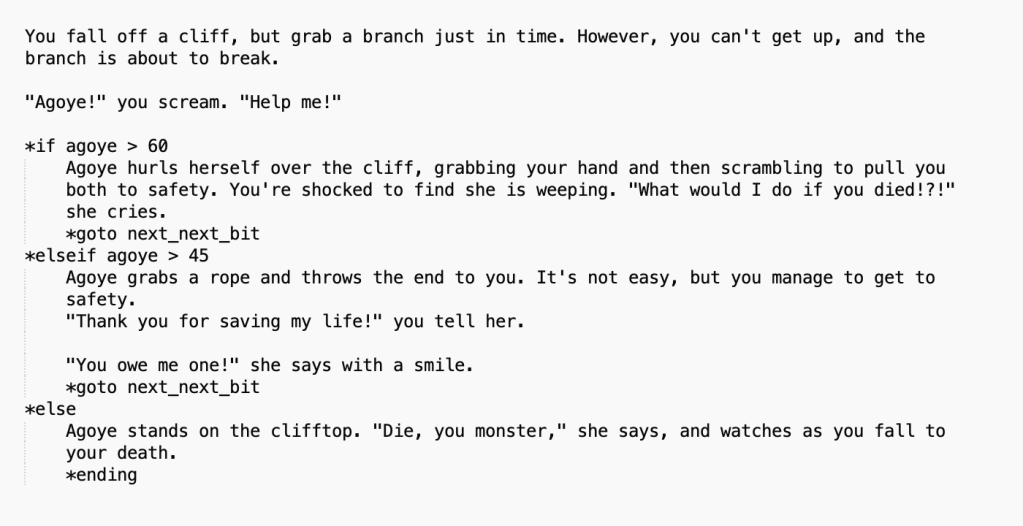

Let’s imagine that instead of swordfighting, this “skill” was how well the player got on with a character named Agoye. This statistic started at 50%, with Agoye feeling neutral towards the player. Depending on the player choices, Agoye may hate them (due to choices that set the agoye statistic with a – instead of a +), love them, or continue feeling neutral. Here’s how a scene might play out towards the end of the game:

Note the command “*ending” which of course indicates an ending.

Writing Tip: In Choice of Games stories, your player must get about three-quarters of the way through the story before dying. “Bad” endings should also be well-written, so the player who chooses to lose on purpose still has a great story experience.

The brilliant thing about statistics is that seemingly minor choices along the way can slowly build up a statistic so that when tested, the player can win or lose in a dramatic (and earned) fashion. Some choices will branch off into unique scenes, but a lot of them will just have a line or two of unique text and/or a statistic. That means they remain meaningful choices without the writer actually going mad writing 100,000 different scenes in each chapter.

STEP SEVEN:

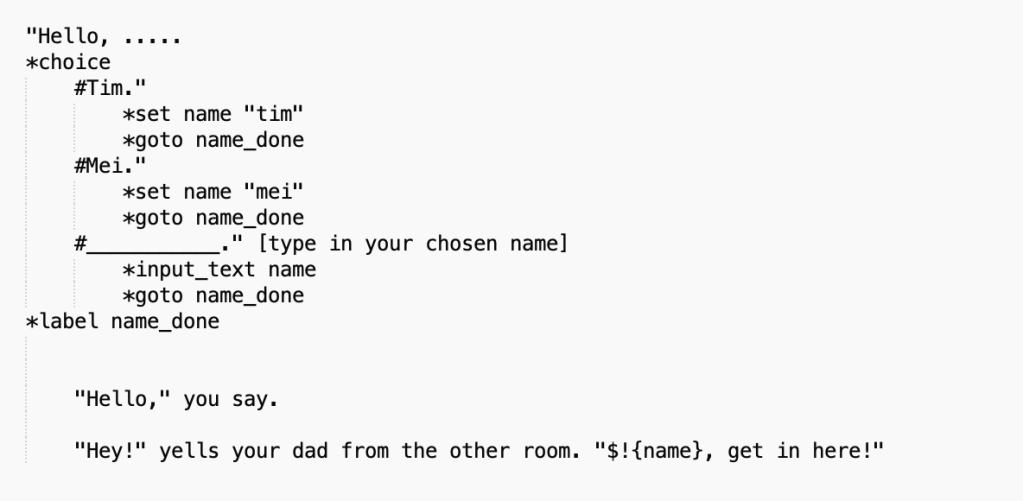

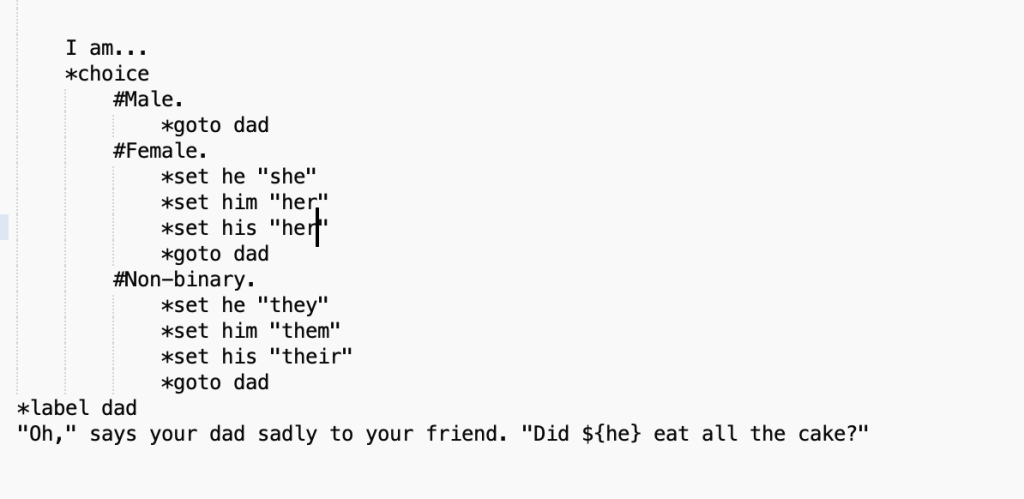

There is one more kind of stat that is important to Choice of Games, and relatively simple to do in ChoiceScript. This is the set of stats that lets a player choose their name and gender. These are boolean stats that include specific text. They are created in the same place as all the other stats—just below the scene list in the “startup” file.

*create name “”

*create he “he”

*create him “him”

*create his “his”

Here is the choice of name (including giving the player the option to type in literally any name they like), and then how to use it. Even though the name is coded is in lower case, using the exclamation mark means it will be capitalised for the reader.

With pronouns, you usually don’t want them capitalised, so it looks like this:

Note that I’ve used male pronouns as the base code. That’s because they’re more straightforward.

Note also that if you include non-binary pronouns (Choice of Games is very focused on diversity—and it’s a kind thing to do—so I recommend it) the grammar will sometimes not work, so you may have to rephrase some sentences.

Eg. you can say, “I took him to the shops” just fine in the various genders (“I took her to the shops”; “I took them to the shops”) but you can’t get, “That dog is his” to work, because “That dog is their” is incorrect.

The distinctions are subtle, so definitely get a native English speaker to check your work!

It is possible to avoid using pronouns for an entire story (I’ve done it) but it’s not easy and it tends to feel awkward to the reader.

Writing Tip: Speaking of gender, Choice of Games also expects you to have a roughly equal number of male and female characters. They will appreciate characters who are non-binary or otherwise gender diverse, too. And every other kind of diversity (IF it is done well! Harmful stereotypes are not appreciated, and if you’re writing about a minority group you don’t know very well then there will be a lot of stereotypes you don’t even realise you hold). You can get Sensitivity Readers, but it’s harder to get them for interactive fiction than regular fiction, and you can’t rely on Sensitivity Readers to fix everything. Also, if your entire plot is offensive then you can’t fix that.

The type of statistic you used to set the player character’s name can be used for other things too. In my cat breeding game, the player can type in unique names for every single kitten.

Leave a comment